|

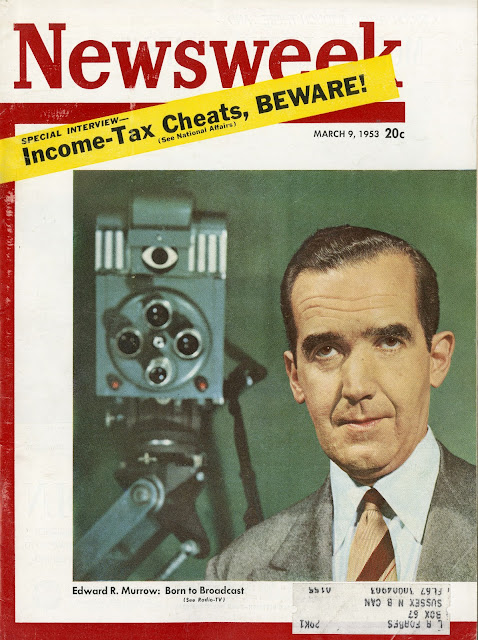

| Newsweek cover featuring Edward R. Murrow, March 9, 1953 (source) |

Edward R. Murrow of CBS: 'Diplomat, Poet, Preacher'

Back in 1948, when saloons that needed clientele were the TV-set manufacturers' best customers, television seers had already announced that a newscaster on radio would soon be obsolete. Television could show the news. These industrial forecasters turned out to be quite as wrong as the political pollsters of that year.

No other medium can touch TV when it comes to describing arranged sight events (political conventions, ball games, dog shows, et al.). But television has not replaced radio in up-to-the-minute, comprehensive news reporting. It is not likely to. A TV commentator can, of course, talk into a camera about the latest news flash. But this is radio news that happens to be on a screen; it is not television news, which by definition requires a picture of the event. Radio can almost always keep higher on top of unpredictable incidents (one definition of one kind of news) than can TV. And, compared to television, which has to pay for mobile units and then stop and add up its time charges and film and cable costs, radio as a news dispenser is quite cheap.

Formula: Du Mont, the smallest American TV network, has never seriously tried to present real news. ABC-TV, always a news-conscious network, attempted to program four and a half hours a week on an $8,000 budget. No go. NBC-TV, with more money and more facilities than any of its rivals, has John Cameron Swayze. As one newspaperman put it: "All NBC needs is Ed Murrow." He was referring, of course, to See It Now, the weekly half-hour TV show on CBS, and, of course, to Edward R. Murrow, the man who narrates it and helps plan it.

Edward Roscoe Murrow (see cover) and his co-producer, Fred Friendly, have devised a formula for TV news that seems to many to be so far unbeatable. After their first show in the fall of '51, Friendly claimed that "we just look good by default." They still do. Long before the premiére, Murrow had come to the conclusion that "there is one thing TV can do—take people places where they're unlikely to get," and See It Now spends no time on studio conversations. Murrow and Friendly make no attempt to handle anything like all the news of the week, or even all the high lights. They choose, instead, to concentrate on a few subjects in their half hour, and, sometimes, to accent the peripheral rather than the main action. Their Eisenhower Inauguration coverage showed street cleaners going to work after the parade and Republicans hunting their cars after the balls were over. Their cameramen are instructed to stick, as far as possible, to close-ups. And the people in the close-ups are supposed to have something to say. The news ideas for the weekly show come from Murrow and Friendly, their crews, their assistants, and their friends. The show has won a Peabody Award and more intelligent and continuing viewers than anybody could shake a really accurate TV yardstick at.

Staff: Few of See It Now's standards could be upheld without a large, active, and talented staff. Four camera crews, each with a photographer and a sound man, work full time for the show. Two reporters, Joe Wershba and Ed Scott, help hold down the news front. All CBS correspondents everywhere are available, and extra footage from News of the Day comes in every week. These people and their equipment cost money. As Murrow puts it: "In this lousy business it costs 500 bucks to take the cover lens off the camera." The sponsor, the Aluminum Co. of America, which can almost always dig up $500, provides some $20,000 a week for the show. CBS has to make up a difference "too often." When Murrow, six other reporters, and twelve camera crews went to Korea to prepare the unforgettable “This Is Korea—Christmas 1952," Alcoa provided an extra $65,000, and CBS anted up $15,000. The network may not be delighted with the financial aspect of See It Now, but, characteristically, it knows a prestige show when it owns one.

An added attraction is the relationship between Murrow and the sponsor. The board of Alcoa bought See It Now after one lunch with Murrow and without seeing an audition film. President I.W. Wilson went farther: He wanted Murrow to report if he objected to any commercial, and he wanted Murrow to delete commercials if the show warranted the time. "I was still curious," Murrow says, "as to what would happen the first time we threw it out. Nothing happened."

Since then, he has dropped it four times—probably creating no bad will for Alcoa. When See It Now presented a report on iron ore (tantamount to Dorothy Collins singing "Be Happy, Go Lucky" on the Camel News Caravan), Murrow never heard a word from Alcoa. On March 8, on their own, Murrow and Friendly are going to produce a commercial for Alcoa free of charge.

Murrow has the same luck with his radio bankroller. The American Oil Co., which sponsors his nightly newscast over most of the country (the Hamm Brewing Co. picks it up in ten Western states), has never objected to Murrow's eliminating Amoco commercials in the interest of the news—something he has done on numerous occasions.

Voice: Murrow, a slim and tall (6 foot 1), dark-haired man with a furrowed brow, is now 44. Christened Egbert Roscoe, near Greensboro, N.C., he moved to Skagit County, Wash., when he was six. His parents still live there, and one of his brothers, Dewey, is a successful contractor in Spokane. His other brother, Lacey, is a brigadier general in the Air Force. Egbert was a chubby, round-faced kid with the biggest voice in Skagit County. He used to tell Dewey that he got the fewest spankings because his neighborhood-wide hollering embarrassed the household. Murrow's latter-day colleague Eric Sevareid called it cold when he said: "Murrow was born to broadcast."

Murrow's first public speech was an unscheduled one at a PTA meeting. Each mother was to make a brief comment on a current problem, and when the chairman called on Mrs. Murrow, little Egbert jumped to his feet to report that he and his brothers had trapped a rabbit the day before and sold it on the way home. The address is said to have made a great success.

The Murrow family was not rich. The senior Murrow, a farmer in Greensboro, became a railroad engineer for a logging company in the state of Washington. Egbert took a year off after high school to earn money to go to college by working in the woods on a survey gang. After his freshman year at Washington State College, he shifted scenery in the school auditorium and served as houseboy at the Kappa Delta sorority house. He was serious-minded, seldom dated, and didn't care for athletics, although he played a little golf. Ed Lehan, now a Spokane attorney, who roomed with Murrow for the four college years, says that "he had a photographic mind. He could sit through classes all week and never take a note, but on Friday nights he could rattle off the professors' lectures almost verbatim."

Egbert changed his name to Edward after his sophomore year, became president of the junior class, and was student-body president as a senior. He was the top cadet in the ROTC, noted for his firm and effective parade-ground voice. He also was the best debater on the campus and the No. 1 man in dramatics. His voice caught the fancy of a little crippled WSC speech teacher named Ida Lou Anderson, who made him her protégé and perhaps did more to perfect his vocal delivery than any other person. When, during the blitz, Murrow was abroad for CBS and broadcast This Is London, Miss Anderson caught every program. Murrow asked her to cable him collect each week with criticisms. She occasionally had some, but always sent them air mail. Miss Anderson, who died during the war, suggested that he put more emphasis on the subsequently sonorous "This." Murrow's present "This is the news" is not only his unregistered trademark but practically antiphonal.

Murrow was 22 when he received his Phi Beta Kappa key and his B.A. in history and speech—his only earned degree (he now has five honorary doctorates). He then became president of the National Student Federation in New York at $25 a week, and made two trips abroad to study. Two years later, he was made assistant director of the Institute of International Education.

Talks: In 1935, Edward Klauber, the executive vice president of CBS and a former New York Times man, hired Murrow as director of talks and education. Klauber, whom Wells Church, now head of CBS radio news, calls "the godfather of the whole damn radio-news business," sent Murrow to London as director of foreign talks. CBS being without any other men abroad, Murrow, with a secretary and an office boy, was the European bureau. He and radio were so unimportant that "I couldn't even go to an American press club meeting, let alone be a member." (He was elected president in 1945.)

At first Murrow merely arranged for important people to speak and set up cultural programs. Then, to combat NBC's more extensive coverage (two men), he hired William L. Shirer. (The CBS staff today is knee-deep in Murrow men; he has since hired Wells Church, Eric Sevareid, Larry LeSueur, Charles Collingwood, Dick Hottelet, Bill Downs, Howard K. Smith, Charlie Shaw, and Cecil Brown.) When Hitler moved into Austria and the authorities refused to let Shirer speak on the air from there, Murrow flew from Berlin to Vienna in a chartered plane, rode a streetcar into town, received permission, and delivered his first news broadcast. Except for one brief period after the war, when he served as vice president in charge of news and public affairs, he has not stopped since. Now a member of the CBS board of directors, Murrow's first love is broadcasting. He has "no mind for budgets, no heart for firing people."

News: Murrow's broadcasts from London during and after the blitz made a great score in the world of the radio-news business. So did his broadcasts, after the United States entered the second world war, from North Africa and Europe. He got to know his top boss, William S. Paley, in wartime London. Paley recalls: "His entrée was just fantastic, and he was full of inside information. Everybody had a genuine respect for him, and they would come clean with him. It seemed he was almost the most important American there."

Since 1945, Murrow, the boy who was born to broadcast, has continued his radio program, except for his short tenure as vice president. He and a staff of five (Jesse Zousmer, his news editor; John Aaron, his researcher; and three girls) turn out a show that is heard by 1,750,000 radio listeners every night. See It Now, according to the Nielsen rating, is seen as well as heard in almost three million homes each week. (When Walter Winchell first went on ABC-TV, his rating was nearly double Murrow's, but he is now below Murrow.)

Features: In addition, Murrow has narrated the three "I Can Hear It Now" albums which Fred Friendly compiled, and introduces This I Believe, the daily five-minute radio program that features prominent people explaining their philosophies. Murrow wrote the introduction to the best-selling book (more than 200,000 copies sold) of the same name that Simon & Schuster published. He conducts the annual CBS year-end show on both radio and television. Last week he was also busy planning a new television program, a live-interview show featuring Murrow talking to newsmaking people throughout America.

Murrow, his handsome wife, Janet, whom he calls Köchin (German for cook), and their 7-year-old son, Charles Casey, live most of the time in a large Park Avenue apartment. Since Casey entered the first grade, he has stopped joining his father on his annual Christmas broadcast. They spend part of each week end at their "log cabin," an eight-room house on a hill near Pawling, N.Y., where Murrow cuts brush, hunts, fishes, and plays golf (sometimes with neighbor Lowell Thomas).

Casey, it is said, was in favor of General Eisenhower in the last Presidential campaign. Who was his father for? Who, indeed, is CBS for politically? Two fifths of his mail accused him of being pro-Ike. Three fifths of his mail called him pro-Stevenson. Murrow's answer to the total criticism of his broadcast content: "Nobody can be wholly impartial, but you must discount prejudice and not reach a conclusion unless you try to trace the facts that led you to it." Murrow is also accused of being gloomy, portentous, and even pompous by some of his most severe viewers and listeners.

Not severe is Fred Friendly, a burly, loose-jointed dynamo of a man who deserves more credit for See It Now than he gets. "I don't kid myself. Even what I do myself, I do in his [Murrow's] name. I can move mountains through him and with him. Whatever Wershba or Scott or I do, we try to live up to Murrow" Friendly, whom Murrow describes as "the only man I know who can take off without warming his motors," was left in New York at Christmastime to cut the 77,000 feet of Korean film down to 6,000. "When I was editing it, I found that my decisions were unconsciously his. With all my exuberance and vitality, I'm coming to understate like him. He's a big spirit; you can't help being dominated."

A civil-defense executive who asked Murrow to narrate an information film explained that he had picked Murrow because there are three voices in the United States that people really listen to—Bishop Sheen's, Arthur Godfrey's, and Ed Murrow's.

Murrow's colleague, Eric Sevareid, wrote of him in "Not So Wild a Dream" in 1946: "He is a complex of strong, simple faiths and refined, sophisticated intellectual processes—poet and preacher, sensitive artist and hard-bitten, poker-playing diplomat . . . He could absorb and reflect the thought and emotions of day laborers, airplane pilots, or Cabinet ministers . . ."

Paley, boss of Murrow as well as of CBS, certainly is satisfied: "Murrow measures up as a broadcaster, a writer, and as a thinker—especially as a thinker—as well as any man I know. He hides, on the job, his own personal feeling, and never takes advantage of his privileged position except maybe from time to time and then unconsciously."

And so, curiously, it is said, is Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy satisfied. He is quoted as observing that he wished every radio and TV commentator were as fair as Ed Murrow.

Murrow may have everything.