The Red Army's Message to German Soldiers at Stalingrad

|

| "A wounded German soldier has a smoke with Luftwaffe pilots before being flown to a hospital. A German controlled airfield. Stalingrad. Winter. 1942." (source) |

In late 1942, the Soviets created this German-language leaflet addressed to Wehrmacht soldiers in the late stages of the Battle of Stalingrad. It taunts them and calls for their surrender, stating that the German army has been routed and warning that those who continue to fight will receive no mercy.

Below is an English translation followed by the original German text. The text is formatted in the same manner as the leaflet.

December 23, 1942:

To the encircled officers and soldiers of the German Wehrmacht in the area of Stalingrad

Soldiers and officers of the encircled German Army in the area of Stalingrad!

You have been encircled for an entire month; a tight ring of Soviet

troops has encompassed you.

You have been hoping for support from the troops, which Hitler has

hastily gathered in the area north of Kotelnikowo.

So know, then, that we have devastatingly beaten them.

In the area of Wassilewka—Werchnje-Kumski—Klykow the Red Army

has overrun and defeated six German divisions, including three tank

divisions, and the remains of said troops have been thrown back 60—85

kilometers. During these fights 278 German planes, 427 tanks and 221

guns have been destroyed. Deaths alone have cost the Germans 17000 men.

Your hope to receive aid from the direction of Kotelnikowo has hereby

been wrecked.

You had hoped that the troops, which Hitler has hastily gathered in

the area of Tormossin, would bail you out.

So know, then, that said troops

have been devastatingly beaten and crushed.

The Red Army has also launched an offensive towards the middle Don,

and during the battles between the 16th and 27th December, has

obliterated 58000 German soldiers and officers, captured 56000 men, 305

tanks, 2128 guns, 310 ammunition and provisions depots have been

captured or destroyed.

Our troops have captured the cities Millerowo, Tormossin, Tazinskaja and Morosowski.

During one month of fighting in the area of Stalingrad and during ten

days of fighting at the middle Don, the German troops have lost

169000

men to death, 128000 men have been captured alongside 2663 tanks and

5356 guns.

Your hopes to receive help from the direction of Tormossin have also been crushed.

You did finally hope to receive help from transport planes.

So know, then, that the Soviet air force and artillery have already

destroyed the majority of the transport planes that were designated to

aid the encircled German troops near Stalingrad.

Between the 25th of November and the 27th of December 765 German planes, including 473 transport planes Ju 52,

have been destroyed in the area around Stalingrad. Additionally Soviet

troops have ruined 30 transport planes at the airfields near Tazinskaja.

Your situation is completely hopeless, and any further resistance is

senseless. Do you still not see that all of your hopes to escape the

pocket are irretrievably gone!

German officers and soldiers!

The Soviet leadership appeals and warns you one last time:

SURRENDER

and you are released from the cold and the hunger. Your life and your personal belongings are safe.

German officers!

You know better than your soldiers that the situation of the

encircled troops at Stalingrad is hopeless, and about the futility of

your resistance. You know very well not to expect any more help.

You can save your soldiers and yourselves by laying down your weapons.

You can not lead the encircled soldiers into ruin. Think about the

fact that, if you do not surrender into captivity, the responsibility for

the demise of tens of thousands of German soldiers will fall on you.

Whoever does not surrender should expect no mercy. He will be wiped

out by our troops. Just one thing is a sure bet during the next days—death!

Surrender before it is too late!

The Commander of the Stalingrad Front

Colonel-General Jeromenko

The Commander of the Don Front

Lieutenant-General Rokossowski

23 December 1942

—————————

This flyer acts as a pass for an unlimited number of German soldiers and officers who surrender to the Russian troops.

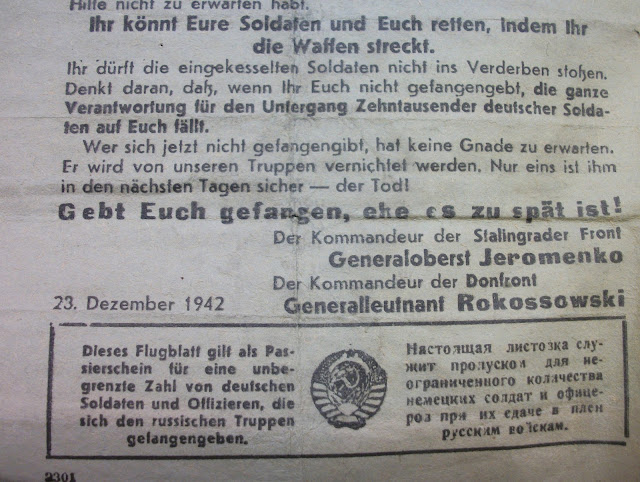

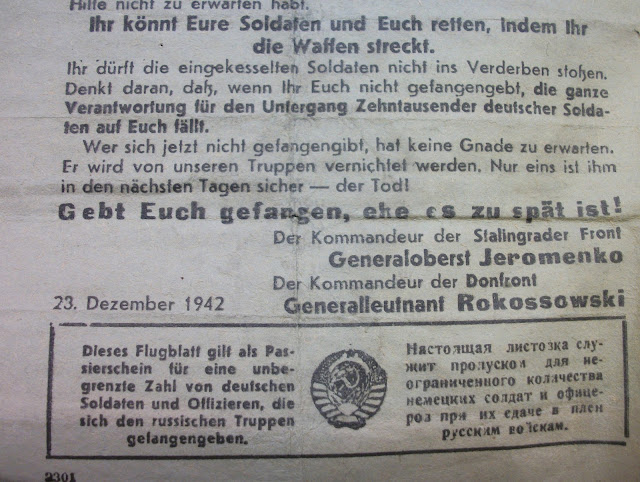

An die im Raum von Stalingrad eingekesselten Offiziere und Soldaten der deutschen Wehrmacht

Soldaten und Offiziere der im Raum von Stalingrad eingekesselten deutschen Armee!

Einen ganzen Monat seid Ihr jetzt schon umzingelt; ein dichter Ring von Sowjettruppen hält Euch umfasst.

Ihr habt auf die Hilfe der Truppen gehofft, die Hitler in aller Eile im Raum nördlich von Kotelnikowo zusammengezogen hat.

So weißt denn, daß wir diese deutschen Truppen vernichtend geschlagen haben.

Im Raum von Wassilewka—Werchnje-Kumski—Klykow hat die Rote Armee sechs deutsche Divisionen, darunter drei Panzerdivisionen, überrannt und zerschlagen, die Uberreste dieser Truppen um 60—85 Kilometer zurückgeworfen und in diesen Kämpfen 278 deutsche Flugzeuge, 427 Panzer und 221 Geschütze vernichtet. Allein on Toten haben die Deutschen hier 17000 Mann verloren. Eure Hoffnungen, aus der Richtung Kotelnikowo Hilfe zu bekommen, sind damit zuschanden geworden.

Ihr habt gehofft, daß Euch die Truppen heraushauen werden, die Hitler in aller Eile im Raum von Tormossin zusammengezogen hat.

So weißt denn, daß auch diese Truppen vernichtend geschlagen und aufgerieben sind.

Die Rote Armee ist auch am mittleren Don zur Offensive übergegangen und hat in den Kämpfen zwischen dem 16 und 27 Dezember 58000 deutsche Soldaten und Offiziere vernichtet, 56000 Mann gefangengenommen, 305 Panzer, 2128 Geschütze, 310 Munitions- und Lebensmittellager erbeutet bzw. zerstört.

Unsere Truppen haben die Städte Millerowo, Tormossin, Tazinskaja und Morosowski erobert.

Während eines Kampfmonats im Raum von Stalingrad und wahrend der zehntägigen Kämpfe am mittleren Don haben die deutschen Truppen

Insgesamt 169000 Mann an Toten und 128000 Mann an Gefangenen sowie 2663 Panzer und 5356 Geschütze verloren.

Eure Hoffnungen, aus der Richtung von Tormossin Hilfe zu bekommen, sind ebenfalls zunichte geworden.

Ihr habt schließlich gehofft, durch die Transportflieger Hilfe zu bekommen.

So weißt denn, daß die sowjetische Luftwaffe und Artillerie bereits den größten Teil jener Transportflugzeuge vernichtet haben, die dazu bestimmt waren, den bei Stalingrad eingekesselten deutschen Truppen Hilfe zu bringen.

Zwischen dem 25 November und 27 Dezember sind im Raum von Stalingrad 765 deutsche Flugzeuge, darunter 473 Transportflugzeuge Ju 52, vernichtet worden. Außerdem haben die Sowjettruppen auf den Flugplätzen bei Tazinskaja 30 deutsche Transportflugzeuge ist zuschanden geworden.

Eure Lage ist völlig hoffnungslos, und jeder weitere Widerstand ist sinnlos. Seht Ihr noch immer nicht ein, daß alle Eure Hoffnungen, aus dem Kessel herauszukommen, unwiederbringlich verflogen sind!

Deutsche Offiziere und Soldaten!

Das Sowjetkommando ruft Euch ein letztes Mal warnend zu:

GEBT EUCH GEFANGEN

und Ihr seid erlöst von Kälte und Hunger. Euer Leben und Eure persönliche Habe ist Euch gesichert.

Deutsche Offiziere!

Ihr versteht besser als Eure Soldaten die ganze Aussichtslosigkeit der Lage der bei Stalingrad eingekesselten Truppen und die Sinnlosigkeit weiteren Widerstands. Ihr weißt ausgezeichnet, daß Ihr Hilfe nicht zu erwarten habt.

Ihr könnt Eure Soldaten und Euch retten, indem Ihr die Waffen streckt.

Ihr dürft die eingekesselten Soldaten nicht ins Verderben stoßen. Denkt daran, daß, wenn Ihr Euch nicht gefangengebt, die ganze Verantwortung für den Untergang Zehntausender deutscher Soldaten auf Euch fällt.

Wer sich jetzt nicht gefangengibt, hat keine Gnade zu erwarten. Er wird von unseren Truppen vernichtet werden. Nur eins ist ihm in den nächsten Tagen sicher—der Tod!

Gebt Euch gefangen, ehe es zu spät ist!

Der Kommandeur der Stalingrader Front

Generaloberst Jeromenko

Der Kommandeur der Donfront

Generalleutnant Rokossowski

23. Dezember 1942.

—————————

Dieses Flugblatt gilt als Passierschein für eine unbegrenzte Zahl von deutschen Soldaten und Offizieren, die sich den russischen Truppen gefangengeben.

Настоящая листовка служит пропускою для неограниченного количества немецких солдат и офицеро пря их сдаче в плен русским войскам.